On this red-figure Athenian amphora, made c.470-450BCE, we see a young warrior being wished well as he leaves for a military campaign. He shakes the hand of an older male figure – perhaps his father – whose hair has been outlined with black slip but not filled in, creating the impression of white hair. The handshake, or dexiosis, with a departing warrior became quite a frequently reproduced scene. With wars flaring up in most years of the classical period it was one that lots of families would recognise from their own lives.

The warrior is well-prepared for his campaign, with a long thrusting spear, a back-up sword, and a traveller’s hat (called a ‘petasos’) to keep sunstroke at bay. A second male well-wisher is in-between the ages of the two central men, bearded but not yet grey. On the far left, a woman prepares to pour a libation. She holds a phiale dish in her left hand and a small oinochoe jug in her right. Like the man on the right, the woman is bent forward to fit neatly into the curve of the vase, accentuating the focus on the warrior.

Source image with permission of Jean-David Cahn AG (www.cahn.ch).

The amphora is the work of an artist known as the Leningrad Painter. He was named after the city (now St. Petersburg) where many of his pieces are housed and where his personal style was first recognised. The Leningrad Painter was an early mannerist painter, working in the early to mid-fifth-century BCE. The mannerists were a group of artists known for depicting somewhat exaggerated gestures and for their fondness for scenes that were unusual or drawn from daily life. The Leningrad Painter in particular is noted for the way he depicts people as tall and slim with relatively small heads.

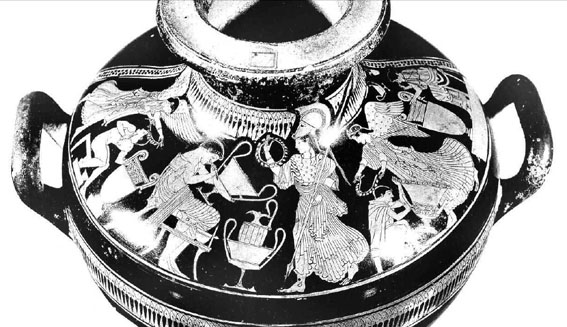

This hydria (Milan, Torno Collection, C278) is also by the Leningrad Painter. He has styled the folds of cloth with more details than he used on the dexiosis vase, yet we can see the similarity in his depiction of the figures’ proportions and in the use of repeating points in the decorative borders. The scene shows a potters’ workshop, where the potters are busy at work, including a female potter (on the far right). They are honoured by a visit from Athena and her companions who are crowning the potters with laurel wreaths symbolising victory and excellence. The Leningrad Painter has imagined potters receiving the sort of recognition normally reserved for victorious athletes, musicians, or generals. They are all honoured, except for the female potter who’s been left out. Her exclusion from the prizes gives us some insight in to possible resentment or disdain towards female co-workers, but her depiction is also interesting evidence of an acknowledgement of female labour in the potters’ workshops of classical Athens.